2025 Recap - Mountaineering and Alpinism in Peru

Franklin Navarro high on Nevado Veronica at dawn with lights from the Sacred Valley down below

I have a new obsession and dreams of grandeur. 2025 has been my best climbing year in Peru yet, making strides in my mountaineering and alpinism experience that included my first ever solo climbs on glaciated terrain and climbing over 6000 meters for the first time when Nate Heald and I made the first ascent of the south face of Nevado Palcaraju in the Cordillera Blanca.

An unusually wet 24/25 rainy season gave me optimism for better than average conditions in Peru’s greater ranges after back to back years where everything was totally dry by the end of June. I knew it was a wet season because every time I called my friend in Huaraz he told me that it was, “raining like a crying woman.” I’d never heard that phrase before but something told me that it had been raining constantly, every day, without reprieve, for several months straight.

In addition to climbing, I made Urubamba my new home. The previous three seasons I lived in Huaraz. It was enjoyable there for chunks of time, and I love spending a month or two each year adventuring in the Blanca, but as a foreigner living in Perú full-time and trying to build a business from scratch, live a fulfilling life, etc. the Cusco region offers drastically more opportunities.

In this article, I share a mix of successes, failures, and scattered reflections from my year in Peru. As always, I’m deeply grateful for the community I’ve found there—friends in Huaraz, Lima, and throughout the Cusco region who make the country feel like home. Life in South America is a gift, and I hope you get something out of this recap of my season of alpinism and mountaineering in Peru.

April - Warming up

I started the season with a couple of failed acclimatization attempts that were meant to prepare me for higher objectives that Nate, Dane, and I planned for May. The first of three was a solo attempt on Nevado Chicon's north ridge. I budgeted two days when I should’ve given myself three. At 4am on day two of the climb I slowly progressed up the chossy volcanic rock at about 50 meters per hour. It felt like every foothold and handhold was ready to pull out at any moment. It was too sketchy to rush and I knew there was no way that I could summit, descend to camp, and hike out to the Sacred Valley all in one day. So I bailed the route at 5300 meters.

Then, Nate and I took four clients to Nevado Pumahuanca but that ended before it even started due to poor viz and rain.

In the last week of the month, there appeared to be one more weather window in the forecast before my trip to Huaraz. My main climbing partner Frank and I decided to make an attempt on Nevado Veronica. We made a high camp on the glacier at 5300 meters on day two to give ourselves the best chance at making the summit. It was 11pm, and we got out of the tent to start the climb after chowing down a quick breakfast (second dinner?). But before we could even start the ascent we noticed that we were surrounded by electrical storms coming from Amazon basin. It was a highly exposed position to be in.

Frank looking to the east at sunrise from high camp, hours before the electrical storms

Flashes of lightning from the electrical storms a few kilometers away

The storms towered over us in the distance. Lightning flashed before our eyes as we contemplated the next move. We decided rather quickly that climbing higher presented too much risk. The summit was off the table. But descending presented risks too. We discussed our options and ultimately decided stay put in the tent until first light hoping that the storms would pass.

Fortunately, the electrical part of the storms missed us, but by 2am we were fully engulfed by a snowstorm. At 6am we broke camp and visibility was limited around five to ten meters. It snowed constantly while we retreated down the mountain without any problems.

Read a more detailed account of the climb and watch my cinematic vlog here.

May - Game on

Nate, Dane, and I stayed at my good friend Jim’s apartment only a couple blocks from the plaza de armas. Jim has been around the Cordillera Blanca since the 80s. He knows more about the area than anyone else and we grateful appreciate him letting us crash at his place while he was in the States. It was a climbers’ dream pad. Mattresses on the floor, pasta dinner’s every night, and the usual shenanigans. After Nate and I successfully climbed Palcaraju (full write up in my blog article here), Dane’s primary objective was to teach me cribbage and show me classic movies when we weren’t out climbing. How had I not seen the Big Lebowski? The Dude! Classic. Thank you, Dane.

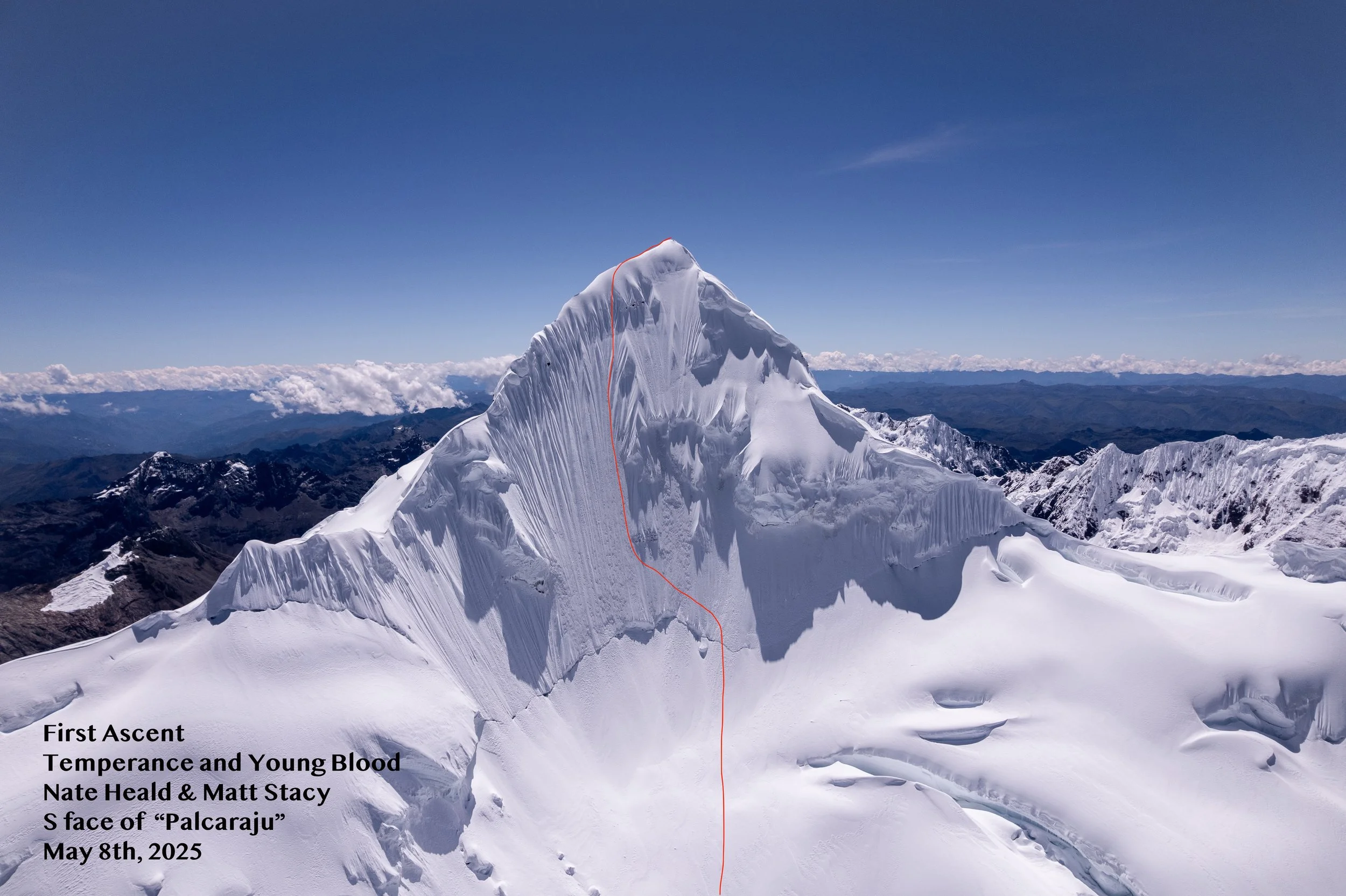

Palcaraju - South Face w/ Nate Heald, 500m AI3 D+

Our route on the south face of Nevado Palcaraju

Nate and Dane on the approach to Camp 1 on Palcaraju

About a week after Palcaraju, Nate, Dane, and I bailed on an attempt of the impotent south face of Chacraraju Oeste. We thought that conditions would be similar to those on Palcaraju, but they weren’t. The first two pitches of the French Direct were near 90 degree snow plaques that were not protectable, meaning a fall would have been very consequential. It got too sketchy and we bailed just 60 meters up the wall on the second pitch. I imagine that thirty years ago there was significantly more compacted snow and ice on the route. Nate went back to Cusco afterward and I made plans with Dane to climb the west face of Tocllaraju and the north face of Ranrapalca before I had to return to Urubamba at the end of the month.

The west summit of Chacraraju

In the third week of May, Dane and I set up base camp in the Ishinca Valley. Our plan was to climb both the west face of Tocllaraju and the north face of Ranrapalca in 5-6 days, both 6000-meter mountains. Unfortunately, I didn’t join either climb due to a bothersome left knee that nagged me at Tocllararaju moraine camp. Dane soloed the route from camp to camp in 8 hours without breaking a sweat. We went down to Refugio Ishinca after he returned from the summit around 10am, hoping that a day or two of rest would give my knee enough time to improve for the attempt on Ranraplaca. Had it not been for plans to guide clients on Nevado Ausangate a couple of weeks later for Nate, I probably would have just climbed and dealt with the consequences later.

However, after a day of rest, my knee still didn’t feel right, and Dane was in excellent condition.

The night after summiting Tocllaraju, Dane left our camp on his own, without a harness, screws, or pickets. He only brought the essentials and a radio for us to communicate in case of an emergency. In one of the most impressive feats of climbing that I’ve ever witnessed in my short climbing career, Dane soloed the 900 meter north face, summited, and downclimbed the NE face. From camp to camp at Refugio Ishinca, it took him only 13 hours to complete. To put that into perspective, teams usually take 8 hours to climb the face, not including the slog to the summit. It was a surreal experience for me to witness my friend climb at that level. I felt like I missed out, but I reminded myself of my long-term goals.

First light from Tocllaraju moraine camp with Nevados Ishinca, Ranrapalca and Ocshapalca in the background

Dane basking in the morning sun after soloing Tocllaraju

June - Finding my stride

After parting ways with Huaraz at the end of May, I set my attention on climbing Ausangate with a group of Nate’s clients. My knee felt significantly better after a couple weeks of rest. It was my first time on the south side of Ausangate. When we arrived at the end of the road just a couple of kilometers from the town of Chilca, we were greeted by some of the most impressive mountain landscapes that I’ve ever seen in Peru. Views of Ausangate, Mariposa, Jatunhuma, and other mountains were inspiring. I’d read stories and heard firsthand accounts of Nate’s adventures in this part of the Vilcanota mountain range, and to finally see it in person was special. It connected so many dots that I made in my mind.

On day four of the climb we reached about 6000 meters on a ridge just south of the ‘Shield’ route. It had been a long morning, and half of the team dropped out by sunrise. My rope team climbed another 140 meters before we then turned around due to general exhaustion from the effects of the altitude on the clients. They were a pleasant group to guide—all of them had positive attitudes that made the five days together enjoyable, even though we didn’t summit.

Next, Frank and I climbed Cerro Soray. It was the first time for both of us. The route is a suitable objective for a beginner climber who has never done any mountaineering, and my goal was to climb it so that I could then guide future clients to the summit. Well, it did not go exactly as planned, but we did make the summit despite our detour which you can read more about in my blog article here.

Carro Soray - North ridge w/ Franklin Navarro, 5.9+ M3 PD

A few days after climbing Cerro Soray with Frank, I lead two clients from Texas to the summit via the standard route.

At that point I started my options a profession in guiding more seriously. For the past year I perssitenly told Nate, “I am not a guide. I do not want to be a guide. And maybe I would do it on occasion to help you out and make some money.” When I started my solo travels over 5 years ago, I made it my goal to build a creative business in the adventure space. I’d seriously ruled out guiding. But after these a couple guided trips this year I started to notice that I actually enjoyed taking people out into the mountains.

July - Full steam ahead

Then came July, arguably my most “productive” month of climbing. It consisted of three successful summits, two which were solos and the other was my most proudly led climb to date, Nevado Veronica at 5911 meters. I’ve had a few “oh s***” moments in my life, but the scariest was on this climb. If you want to know more about it, read my article or watch the YouTube video here.

My first solo climb was on Nevado Sirijuani. This is a seldomly climbed peak in the Urubamba mountain range just above the sacred valley. There are a couple different ways to approach the N face, the best being of the small village of Quiswarani. Although it wasn’t the most technically challenging climb, I felt satisfaction to have gone adventuring to a 5400+ meter mountain on my own, completely dependent on my own whits. Here’s a blog article and video I made about that climb.

Nevado Sirijuani - Northwest face, solo, PD

I rested for a couple of days after climbing Sirijuani before making another attempt on Nevado Veronica. Frank and I were in excellent shape for the climb. Normally it takes about 5-6 hours to reach base camp from the road (Abra Malaga). We arrive to camp in just under 4 hours. Climbing to the summit of Veronica was surreal; the views of the sacred valley, the high quality of snow and ice conditions, and the first time I lead a climb of this difficulty from top to bottom. It was my proudest climb to date. For more details about Franklin and I’s success, read the article and watch the cinematic blog here.

Nevado Sirijuani from the village of Quiswarani

Nevado Veronica - East ridge w/ Franklin Navarro, 600m from high camp D

At the end of the month, I needed to get out of the Sacred Valley for a breath of fresh air, so I lugged my gear over to Luis Crispin’s house in Pacchanta with the intent of soloing one or two routes over a week’s time.

First, I attempted to climb a seldomly climbed mountain called Percocaya, which you likely won’t find on any maps. The mountain itself is nothing spectacular to look at, especially with its neighbor, Ausangate, looming 6300 meters above it. My objective was to climb it in a day and bivouac on the summit to witness Ausangate’s north face light up at sunrise. I didn’t summit because by 4:30pm I was still a couple hundred meters shy of the summit. Two years ago, Nate told me there was a purely rock route. Even when I flew my drone, I couldn’t find the line that he referred to. The east face was a labyrinth of cracks and slabs that didn’t make a coherent route to the summit. I knew that I knew I wouldn’t be able to navigate in the dark, so I bailed and decided I’d go back to climb it via the south glacier another time.

My second climb was the south ridge of Jampa. Due to some personal issues that I was facing, it was mentally more of a challenge than Sirijuani. At 2:30am I almost stayed in the tent, contemplating the thought of packing up my tent and descending down to Luis’ house. I’m glad I didn’t because the southwest ridge was a fun outing. Read about it and watch my cinematic blog here.

Nevado Jampa - Southwest ridge, solo, 610m from base camp PD+

Nevado Ausangate’s north face at sunset

July was a solid month for me. It was an example of what I can do when I’m in strong physical condition and focused on my objectives.

August - Slowing down

Unintentionally, August was a bit slow. I guided Cerro Soray for the second time, taking two Canadians from Montreal, who’d never been camping before, to the summit. Then, I attempted Sahuasiray with Franklin, but we didn’t even make it onto the glacier because the intended route was too dangerous with overhead rockfall hazard. I identified an unclimbed line from our high point on the moraine. It looks like it would be a king line, so Frank and I will be back to attempt it in 2026.

Clouds spilling into the Urubamba mountain range from the Amazon basin at dawn

September - Work & trekking

I guided Pumahuanca again but had to turn around due to slow progress with the client. He had a fantastic attitude about the whole thing. It was delightful to see Mario again, the local whose kitchen we sleep in before climbing.

After Pumahuanca, I had commercial video work for a client based out of London. Shooting and editing took a lot of my time in the middle of the month.

Then, I took a break from editing my client’s deliverables to guide a friend, Trey, from my university on the Huayhuash alpine circuit at the end of the month into early October. I celebrated my 29th birthday during an adventure, continuing a tradition I have followed for 5 of the past 6 years. If you want to see more photos from the circuit, visit this article that I wrote.

October - Trekking and return to the USA

Lastly, I guided a trek to Machu Picchu via the ‘secret’ Salkantay alternative. It’s the best trek that exists to Machu Picchu and it is completely private. Nate’s homestead in the valley is incredible and I highly recommend reaching out to me if you want to experience one of the most unique places on our planet that is practically untouched by humans.

Dense cloud forest seen from Nate’s homestead

Lush valley leading to Machu Picchu

I don’t disclose this location’s name because the idea is not to blow it up with corny Instagram influencers. The only trail that goes though this valley is completely PRIVATE, and therefore, trekking agencies are not allowed to operate unless given permission by the residents of the valley. For those interested in a photography expedition to this location, check out my agencies’ website (we have exclusive access).

Final Thoughts - Reflections on other important topics

This journal entry wouldn't be complete without sharing some issues I’ve pondered throughout the year.

Addictive screens pollute modern society, consequently disconnecting us from the real world. I frequently see children as young as 3 years old scrolling on TikTok, and young students relying on ‘AI’ to do their homework rather than building critical thinking skills necessary for adulthood. Simultaneously, excessive consumerism is overwhelming cultures worldwide, with greedy individuals and corporations acting like leeches, snatching away people's dignity without any remorse—all in the name of their financial statements. A particularly subtle, yet disheartening example of where I’ve witnessed the degradation of culture is in Perú’s remote indigenous communities, where on several occasions I observed traditional Peruvian beverages being replaced by liters of sodas. Though it seems like a small change, it highlights the far-reaching impact of global corporations even in the remote regions of the Andes.

I also heard firsthand accounts of tour agencies that compete to offer the lowest price possible to tourists, in turn treating their staff like they are less than human by paying them below living wages and feeding them cheap food that they wouldn’t dare feed their customers. It begs the question, why aren't the staff members for these companies treated with the same respect as the clients? How can we hold these people accountable for labor exploitation? And how can we raise the standards of business operations across the industry?

These are just some ideas that have weighed on my mind throughout the year. I’m optimistic. I have hope for a better future. We can choose to support our local communities by buying products produced by our neighbors. We can foster human connection by looking each other in the eyes and giving smiles to passersby. We can slow down and take time to learn the names and stories of the people in our communities. We can live more intentionally. And we can connect with nature to remind us where we come from. We are vibrant souls that are capable of tuning into the same frequencies. We can hear each other’s differences, respect one another’s opinions, and live in harmony more easily than it seems.

So although this was my “best” mountaineering and alpinism year in Perú, my takeaway for 2025 is one of gratitude, identifying the problems I see in the world, and doing what I can to be an agent of change. Thank you for taking the time to read this journal, completely written by me, a human. I wish you a fulfilled year and look forward to the adventures we will share together in 2026.